The first, of what I am sure are many, analytical diagrams focusing on the site. I chose to do a figure ground diagram to isolate the key elements and look at their relationship together. The objects left in white (the residential, military, and religious structures of the historical district) can be more easily defined by their physical relationships, scale, and overall organization. However, an even more significant relationship can be observed through this diagram. That is the relationship that exists between the community and the ocean. I found that in plan there is a subtle elegance to the composition of the different "pieces." I believe this elegance exists in much more than just the plan of the design. I believe it to be this very characteristic that has inspired the groups opposing demolition to fight so intensely to have this neighborhood saved. Whatever the future design for the neighborhood entails, it must retain this elegance if it is to be successful.

The first, of what I am sure are many, analytical diagrams focusing on the site. I chose to do a figure ground diagram to isolate the key elements and look at their relationship together. The objects left in white (the residential, military, and religious structures of the historical district) can be more easily defined by their physical relationships, scale, and overall organization. However, an even more significant relationship can be observed through this diagram. That is the relationship that exists between the community and the ocean. I found that in plan there is a subtle elegance to the composition of the different "pieces." I believe this elegance exists in much more than just the plan of the design. I believe it to be this very characteristic that has inspired the groups opposing demolition to fight so intensely to have this neighborhood saved. Whatever the future design for the neighborhood entails, it must retain this elegance if it is to be successful.

Monday, September 21, 2009

Site Diagram

The first, of what I am sure are many, analytical diagrams focusing on the site. I chose to do a figure ground diagram to isolate the key elements and look at their relationship together. The objects left in white (the residential, military, and religious structures of the historical district) can be more easily defined by their physical relationships, scale, and overall organization. However, an even more significant relationship can be observed through this diagram. That is the relationship that exists between the community and the ocean. I found that in plan there is a subtle elegance to the composition of the different "pieces." I believe this elegance exists in much more than just the plan of the design. I believe it to be this very characteristic that has inspired the groups opposing demolition to fight so intensely to have this neighborhood saved. Whatever the future design for the neighborhood entails, it must retain this elegance if it is to be successful.

The first, of what I am sure are many, analytical diagrams focusing on the site. I chose to do a figure ground diagram to isolate the key elements and look at their relationship together. The objects left in white (the residential, military, and religious structures of the historical district) can be more easily defined by their physical relationships, scale, and overall organization. However, an even more significant relationship can be observed through this diagram. That is the relationship that exists between the community and the ocean. I found that in plan there is a subtle elegance to the composition of the different "pieces." I believe this elegance exists in much more than just the plan of the design. I believe it to be this very characteristic that has inspired the groups opposing demolition to fight so intensely to have this neighborhood saved. Whatever the future design for the neighborhood entails, it must retain this elegance if it is to be successful.

Monday, September 14, 2009

Concept Sketch 3

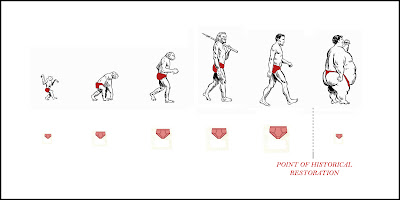

Since the decommission of the Fort Kamehameha historical houses, the true definition of the buildings has been lost. They cease to serve the purpose for which they were created. There are no residents whom occupy the houses. They sit vacant in a quiet, abandoned site. However the debate of the houses has never been louder. There are multiple groups, organizations, and institutions that have formed their own definitions of the structures of Fort Kamehameha. The Air Force defines the units as an unnecessary expenditure and a risk. The Hawaiian Historical Foundation defines the buildings as historically significant structures. I, like so many others who have had the privilege of living in the houses, define the buildings as home. It has become necessary to redefine the buildings. An ultimate redefinition, in which all parties involved accept, is necessary in order to once again give life and meaning to these houses. Architecture ceases to be architecture when it is no longer employed. Without a redefinition of these buildings, they will remain in a state of isolation, uncertainty and despair.

Reading Response 2

Monday, September 7, 2009

1 3 9

Historical buildings are better served by their adaptation and continued use than by preserving them in a state of antiquity.

A shift needs to occur in the way that historical buildings are viewed and their preservation is approached. A creative transformation that keeps a historic building operating to meet today’s needs while retaining its historical integrity not only preserves the building’s historical significance, but also preserve’s the buildings dignity. Restricting the building from growing and adapting to accommodate new uses and evolving programs creates an artificial environment that fails both the user and the building itself.

Every good designer will envisage his/her building adapting, over time, to ever changing contextual demands. Unavoidably, buildings follow the designer’s prediction of change as its contexts transform often in unpredictable ways. However, overtime, the users, and others affected indirectly by the building, grow a bond with the edifice, and a feeling of nostalgia is created. This nostalgia creates an urge to defy the designer’s intent for change and return the building to its original condition, contradicting the designer, the user’s needs, and the relative contextual demands. The building ceases to be architecture; it enters the realm of historical monument. Architecture serves the needs of its users and its surroundings. Monuments serve as testaments to a former event or idea, nothing more. This nostalgic antiquarianism leads to a contradiction of everything that represents the building: the architect/designer, the user, and the surrounding environment.